Share This Post

Post Updated

Depression is a word we use often, but it doesn’t point to one single experience. Two people can both say “I’m depressed” and mean very different things — not because one is exaggerating, but because there are distinct patterns beneath the surface of that word.

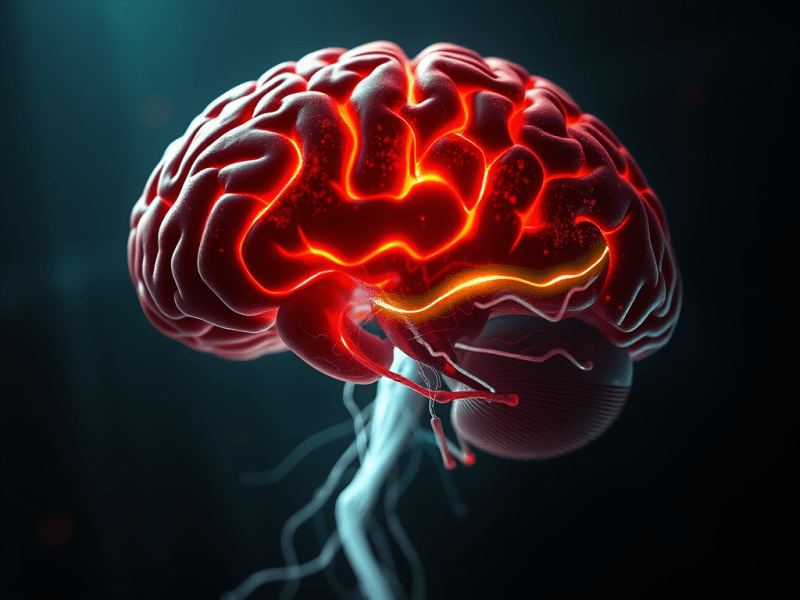

Depression tends to emerge when the nervous system, stress biology, and life context intersect in ways that overwhelm a person’s ability to regulate mood, motivation, and meaning. What looks like “sadness” on the outside can reflect deeper biological processes: disrupted sleep, chronic stress signaling, reduced reward responsiveness, or prolonged emotional overload.

Understanding the major types of depression helps shift the conversation away from blame and toward clarity:

Not just “What’s wrong with me?”

But “What kind of depressive pattern is this — and what does it reflect biologically, emotionally, and socially?”

If you’re interested in how neurobiology shapes emotional distress more broadly, you may find this foundational piece helpful:

The Brain’s Alarm System

Why “Types” Matter

Depression is not one single mechanism. It is often a shared outcome that can reflect different underlying patterns, such as:

- stress systems stuck in overdrive

- neural circuits that struggle to sustain motivation

- circadian rhythm disruption

- inflammatory signaling in some individuals

- social pain registering as real threat

That’s why depression can look different from person to person — and why recovery is rarely one-size-fits-all.

A Little-Known Aspect of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder — Even if You Have It

Discover a little-known aspect of PTSD—how increased complaining can signal heightened symptoms. Learn to recognize the signs, manage overwhelm, and find coping strategies to improve mental well-being.

Keep readingFour Common Forms of Depression

These are among the most widely discussed depressive conditions in clinical settings and modern mental health research.

1) Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

This is what most people mean when they say “clinical depression.”

Major depressive disorder involves a depressive episode lasting at least two weeks, with symptoms present most of the day, nearly every day, and significant impact on daily functioning.

Common features include:

- low mood or emotional numbness

- loss of interest or pleasure

- fatigue and slowed thinking

- appetite or sleep disruption

- hopelessness or worthlessness

Major depression is not a lack of willpower. It reflects real changes in mood regulation systems under sustained strain.

If you’ve ever experienced anxiety arriving suddenly and without warning, you may recognize how biology can reshape experience faster than logic can explain:

When Anxiety Strikes Out of Nowhere

From Shame to Strength: A New Relationship With Depression

Explore how shifting from shame to strength reshapes life with depression. Learn how self-compassion creates resilience and a healthier outlook.

Keep reading2) Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia)

Persistent depressive disorder is often described as long-term depression that becomes a baseline.

Symptoms may be less intense than major depression, but they last much longer — typically two years or more.

People often describe it as:

- “I’ve always felt this way.”

- “Life feels muted.”

- “I function, but I don’t feel fully alive.”

Because it becomes familiar, it’s easy to miss — and yet it can quietly erode hope and quality of life over time.

3) Bipolar Depression

Bipolar depression can look almost identical to major depression — but it occurs within bipolar disorder, which also includes periods of:

- mania, or

- hypomania (a milder elevated state)

This distinction matters because treatment differs. Antidepressants alone are not always appropriate in bipolar disorder and may worsen symptoms for some individuals.

When someone’s mood history includes shifts in both directions, it points to a different underlying pattern.

4) Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD)

Some people find their depressive symptoms follow a seasonal rhythm, most commonly emerging in winter.

Seasonal affective disorder is strongly connected to circadian rhythms and light exposure, not weakness or mindset.

Symptoms may include:

- low energy

- increased sleep

- carbohydrate cravings

- heaviness that lifts in spring

SAD reminds us that mood is deeply biological — tied to the body’s internal clock as much as to life circumstances.

10 Simple Practices That Strengthen Your Mental Health

Mental health is a fundamental aspect of our humanity that can be nurtured daily through simple practices. Recommendations include physical movement, morning sunlight exposure, social connections, reducing noise, and choosing whole foods. Additionally, setting boundaries, reconnecting with nature, limiting digital use, and allowing guilt-free rest promote overall well-being. Start with one small change for lasting…

Keep readingOther Depression-Related Conditions That Matter

The categories above are not the full picture. Several other mood conditions deserve awareness.

Perinatal Depression

Depression during pregnancy or after childbirth is real, common, and serious.

It is not simply “baby blues,” and it deserves support rather than judgment.

Depression With Psychotic Features

In rare severe cases, depression can include psychotic symptoms such as delusions or hallucinations.

This should be treated as a medical emergency and requires urgent professional care. It reflects the depth of disruption depression can create when suffering becomes extreme.

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)

PMDD is a severe cyclical mood disorder closely tied to hormonal sensitivity in the menstrual cycle.

It is more intense than typical premenstrual symptoms and can significantly disrupt mood, energy, and interpersonal stability.

Mental Illness Is Not Invisible — Why I Wrote Wired to Be Human

Mental illness is not invisible. From withdrawal to brain inflammation, symptoms are real and observable. Discover why in Wired to Be Human.

Keep readingDepression Is Not Just Emotional — It’s Nervous-System Deep

One of the most damaging myths is that depression is “just sadness.”

Depression is often associated with:

- nervous-system exhaustion

- prolonged stress physiology

- social disconnection registering as threat

- circadian disruption

- biological withdrawal after overload

That’s why connection is not a luxury — it’s biology.

This theme is central to your broader work on modern life and mental health, including the social survival needs explored in Wired to Be Human.

Related reading:

Why Being Noticed Matters for Mental Health

What Can Help

Because depression is not one thing, treatment is rarely one thing.

Evidence-informed approaches often include:

- psychotherapy (CBT, interpersonal therapy, behavioral activation)

- medication when clinically appropriate

- structured sleep and light exposure

- movement and nervous-system regulation

- rebuilding social safety and connection

A thoughtful plan, ideally developed with a clinician, respects both the biology and humanity of depression.

Explore More Depression Writing on TRTMW

If you’d like to explore more reflections and lived-experience writing on depression, you can browse the full archive here:

Depression Articles from The Road to Mental Wellness

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2023). Screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/clinical-practice-guideline/articles/2023/06/screening-and-diagnosis-of-mental-health-conditions-during-pregnancy-and-postpartum

Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., Salanti, G., Chaimani, A., Atkinson, L. Z., Ogawa, Y., … Geddes, J. R. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 391(10128), 1357–1366. https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(17)32802-7/fulltext

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Bipolar disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Major depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Perinatal depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/perinatal-depression

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymic disorder). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/persistent-depressive-disorder-dysthymic-disorder

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Seasonal affective disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/seasonal-affective-disorder

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2022). Depression in adults: Treatment and management (NICE Guideline NG222). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222

Osimo, E. F., Pillinger, T., Rodriguez, I. M., Khandaker, G. M., Pariante, C. M., & Howes, O. D. (2020). Inflammatory markers in depression: A meta-analysis of mean differences and variability in patients and controls. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 901–909. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7327519/

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Major depression with psychotic features. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000933.htm

World Health Organization. (2023). Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression